Yesterday we had another meeting of the various chairpeople of the Representative Assembly, and afterwards I took advantage of being in southern Kawasaki to visit a couple of the shrines there. One of them, Wakamiya Hachimangu, is a little notorious, due to the nature of a second shrine found in the grounds, so the pictures in this article may not be entirely safe for work, or for those of an exceptionally sensitive disposition. On the other hand, both shrines have kindergartens in the grounds, so they can’t be that bad. To avoid offending people unnecessarily, however, you have to click on the “more” link to see the whole of this article.

I doubt I lost many people there. The first of the two shrines I visited was Nyotai Daijin. This shrine is very close to Kawasaki station, just behind the Lazona shopping centre to the north of the station, but I wasn’t previously aware of it. I bought a guidebook, published by the Kanagawa Shrine Association, that lists the more important shrines in Kanagawa, which is how I found out about it. When I got there, two things struck me immediately. One was that there were dozens of children in the precincts, and the other was that there was a fence across the entrance under the torii. When I got closer, I could see that the sign on the fence said that there was no entry for purposes other than worshipping, because the shrine precincts were also the playground for the kindergarten attached to the shrine. This, of course, also explained the children.

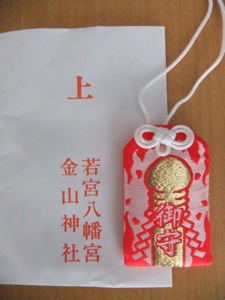

Since I was going to pay my respects at the shrine, I went in and performed the basic ceremony. Then I asked at the shrine office whether they did Goshuin, the red stamps unique to each shrine, and they did, so I asked for one in my book. It takes a little while to do a Goshuin, because, although the red stamp itself is just a stamp, the shrine staff also write the shrine name, the date, and sometimes something else as well, by hand, using a brush. They are, I think, the most appropriate souvenirs of shrine visits, because o-mamori and o-fuda (amulets and tablets) are religious items, not really just souvenirs; the goshuin is, as I understand it, formal proof that you visited the shrine, and that’s something I certainly did. Anyway, while I was waiting, the shrine staff brought me a glass of tea, which has never happened before. When the young man I presume was a priest came back with my book, we had a short conversation about the kindergarten.

Apparently, back in the Edo period, the shrine hosted a terakoya, a sort of private elementary school, so it had a long tradition of providing education. The kindergarten is a continuation of that. As well as using the shrine precincts as the playground, they also appeared to be using a building that was built for kagura (sacred dance) as part of the kindergarten buildings. There were a slide and climbing frame at the sides of the precincts, and the results of the children’s crafts and paintings were spread out in front of the main shrine building. The atmosphere was very much “kindergarten with a shrine attached”, rather than vice versa, although if you went while the children weren’t there, it might be a bit different. The whole place felt like a family activity, and I really liked the atmosphere.

There are five kami enshrined there, but three of them were brought from other shrines about fifty years ago. The two main kami are Izanagi and Izanami, the married kami who gave birth to the Japanese islands and many other kami in the Kojiki and Nihonshoki legends, and gave birth to Amaterasu in the Nihonshoki version. The shrine’s name means “Woman’s Body”, and it is locally known for prayers for safe delivery, home safety, and good relations between husband and wife. Izanagi and Izanami are very appropriate kami for this, as their legend is about family, marriage, and childbirth. However, the name of the shrine doesn’t seem to have much to do with them.

There are five kami enshrined there, but three of them were brought from other shrines about fifty years ago. The two main kami are Izanagi and Izanami, the married kami who gave birth to the Japanese islands and many other kami in the Kojiki and Nihonshoki legends, and gave birth to Amaterasu in the Nihonshoki version. The shrine’s name means “Woman’s Body”, and it is locally known for prayers for safe delivery, home safety, and good relations between husband and wife. Izanagi and Izanami are very appropriate kami for this, as their legend is about family, marriage, and childbirth. However, the name of the shrine doesn’t seem to have much to do with them.

The name is explained by the shrine’s founding legend. The shrine is quite near the mouth of the Tama River, and was closer in the past. The legend says that, after very heavy rains, the Tama and Tsurumi rivers both flooded, drowning all of the land between them. A brave woman, who couldn’t bear to see the suffering, threw herself into the water, and thus calmed the water kami. After that, there were no really serious floods, and the grateful people built a small shrine to honour the woman, which developed into the current shrine.

This sort of legend is also found in the Nihonshoki legends, in the story of Yamato Takeru. When he was trying to cross from the Miura peninsula, not too far from Kawasaki, the sea was so rough that he thought he would have to turn back. His wife, however, threw herself into the water, and the storm quietened. Later, her comb was found on the shore, and placed in a shrine. These legends are thought, for obvious reasons, to derive from old traditions of human sacrifice.

So, considering the name of the shrine and the legend, I suspect that the shrine was originally concerned with preventing floods and getting appropriate amounts of rain, but was called “Woman’s Body” shrine because of the origin legend. Thanks to the name, it became associated with prayers for things that concerned women, such as childbirth and the family. Later, when it became necessary to specify which kami were enshrined, Izanagi and Izanami were chosen, as appropriate to the prayers the kami was supposed to answer. That may have happened as late as the nineteenth century, but without talking to the shrine staff in detail I can’t be sure.

Appropriately enough, we now move from women’s bodies to men’s. The second shrine I visited was Wakamiya Hachimangu, but it is far more famous for another shrine on the grounds, Kanayama Jinja. The shrine’s name is written with the characters for “metal mountain”, and the kami are Kanayama Hiko and Kanayama Hime. “Hiko” indicates a male kami, while “hime” indicates a female one. As their names would suggest, they were originally honoured as the kami of metal work, and particularly popular with blacksmiths. However, this particular shrine gained other associations.

Kawasaki started as one of the way stations on the Tokaido, the main road from Tokyo to Kyoto. The way stations catered to travellers, and so provided food, board, and women. The women started praying at this shrine, for improved business and protection from sexually transmitted diseases, and this slowly broadened to include prayers to have children, safe delivery, finding a husband, and good relations between husband and wife. However, the sexual associations did not disappear, and in recent years the shrine has also become known for its connection to AIDS prevention.

There is a hall for ema, votive plaques, in front of the shrine, and most of them are indeed requests for children, or thanks that a child has been born, at least if my totally unscientific sample was representative. On the ground in the centre of the ema hall is an anvil, as is appropriate to kami of blacksmiths. The anvil is not, however, completely conventional, as you can see from the picture, and there are ema pictures in the obscene style of certain ukiyo-e pictures on the ceiling; penises in monk’s robes, and a picture of the seven gods of good fortune in their treasure ship where all the male gods are penises and the lone goddess looks very pleased. There’s also a picture of five monkeys. In addition to the standard “See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” triad, there are also “transmit no evil, receive no evil” monkeys, covering their genitals and bottoms respectively.

The shrine is still known for ceremonies connected with child birth. Indeed, while I was there a woman came to book a Hatsumiya mairi (first shrine visit), and couldn’t have her first choice of time because another one was already booked. It is also known for the Kanamara Festival, on the first Sunday in April, which is the festival of the Kanayama Shrine, and involves giant penises on the mikoshi.

I received a goshuin at this shrine as well, and talked a bit to one of the staff while I was waiting for it. We, naturally, talked about the Kanamara Festival, and she said that a lot of foreigners come to see it, by the bus load. My feelings about that are a bit complicated. On the one hand, this is not really surprising. American and European religious festivals do not normally involve model penises the size of a (smallish) adult. Further, this is just as much a part of Shinto traditions as any other festival, and I don’t agree with the people who would like to write this sort of thing out of Shinto’s history and current state. On the other hand, it’s no more a part of Shinto traditions than the Grand Festival at Shirahata-san, and I’m the only foreigner who goes to that. If you only visit the Kanayama Festival, it creates a distorted picture of Japan, and of Shinto. You get this a lot. In an article in the Guardian to mark Tokyo being voted readers’ favourite foreign city, the author talks about Meiji Jingu and feels the need to mention that the miko were traditionally virgins. Maybe, traditionally (although I’m not sure about that, as it happens), but it certainly isn’t expected these days. I’m sure this is inevitable. Sex is interesting, so things connected to sex are interesting things to mention. However, it quite possibly contributes to an impression that all other cultures are more obsessed with sex than your own is.

Anyway, the main shrine at Wakamiya Hachimangu enshrines Nintoku Tenno. This is not Hachiman, despite what the name of the shrine might initially lead you to believe. When I was told that, my immediate reaction was “Oh, that’s why it’s Wakamiya”, which provoked a slightly surprised “Oh, are you a Shinto specialist, then?”. I said not really, not yet at any rate, but I don’t think the connection is common knowledge.

This is the connection. Hachiman is commonly identified with Ojin Tenno, who was Nintoku Tenno’s father. “Wakamiya”, written with the characters for “Young Shrine”, indicates a shrine to a child of the kami of the main shrine. Thus, “Wakamiya Hachimangu” indicates a shrine to the child of Hachiman, not to Hachiman himself.

As a result, the shrine precincts include a shrine dedicated to a married couple of kami (Kanayama Hiko and Kanayama Hime) who have become associated with sex and reproduction, and with a kami who is enshrined as the child of another kami. It is, therefore, perhaps unsurprising that the shrine is particularly associated with children and families, and has an attached kindergarten.

The main shrine also seems to be associated with the production of alcohol, although I’m not sure where that comes from. It may just be due to the fact that the establishments at the Tokaido way station sold alcohol to travellers, and the manufacturers prayed for success at this shrine. In any case, this shrine seems to be strongly associated with having a good time.

These shrines are both good examples of the individuality of Shinto shrines. Most do not have kindergartens, and a slide is not normal furniture for the shrine precincts. Similarly, the liturgy for the standard festivals produced by the Association of Shinto Shrines most definitely does not include giant penises. As I say almost every time, this variety is one of the things I find very appealing about Shinto.

Leave a Reply