A kamidana is a Shinto household shrine to the kami. According to a 2009 survey (reported in Ishii 2010 『神道はどこへいくけ』, page 21), about 43% of Japanese homes have one, although only 28% have one in the 14 largest cities. Since most of Japan’s population lives in the 14 largest cities, this means that kamidana must be very common in more rural areas. They are an important part of Shinto practice, but a bit difficult to find out about in English. However, one of the important jobs at New Year is taking everything off the kamidana, cleaning it, and then putting everything back on, with new o-fuda. (I’ll explain o-fuda below.) That provided a good opportunity to take lots of photographs to use in this blog entry.

“Kamidana” literally means “kami shelf”, and the name is accurate, as the traditional kamidana is, indeed, a shelf. The photograph shows the shelf part. As you can see, it is set high on the wall, and the base of the shelf is supposed to be slightly above eye level. You should put it in a clean part of the house, and not in one of the busiest parts. It shouldn’t be over a door, for example. Normally, it should face either east (to the sunrise) or south (to the noonday sun), but ours faces west, because of the layout of the flat, and because you can see Mount Fuji in that direction, from the room the kamidana is in.

“Kamidana” literally means “kami shelf”, and the name is accurate, as the traditional kamidana is, indeed, a shelf. The photograph shows the shelf part. As you can see, it is set high on the wall, and the base of the shelf is supposed to be slightly above eye level. You should put it in a clean part of the house, and not in one of the busiest parts. It shouldn’t be over a door, for example. Normally, it should face either east (to the sunrise) or south (to the noonday sun), but ours faces west, because of the layout of the flat, and because you can see Mount Fuji in that direction, from the room the kamidana is in.

The shelf does not normally extend all the way to the ceiling, but ours is quite deep, and to keep it above my eye level, it had to be fixed to the ceiling. Even then, the base is really at my eye level; I’ve walked into it a couple of times, and whacked myself on the temple. Fixing it to the ceiling is a slight problem, because it means that there is no easy way to hang a shimenawa (sacred rope) from the top. We are thinking about adding a couple of hooks.

The decoration in the wooden panel across the top of the kamidana is, I think, supposed to look like clouds, because you are supposed to put it somewhere where no-one will walk over the top of it. However, in blocks of flats, that is impossible, unless you live on the top floor. Since most Japanese people live in flats, Shinto priests have come up with a workaround. You stick the chinese character that means “clouds” to the ceiling over the kamidana (ours is wooden, and stuck just inside the front of the shelf). This apparently fools the kami into thinking that it’s the sky above them, or maybe mollifies them because you’ve obviously made an effort.

The decoration in the wooden panel across the top of the kamidana is, I think, supposed to look like clouds, because you are supposed to put it somewhere where no-one will walk over the top of it. However, in blocks of flats, that is impossible, unless you live on the top floor. Since most Japanese people live in flats, Shinto priests have come up with a workaround. You stick the chinese character that means “clouds” to the ceiling over the kamidana (ours is wooden, and stuck just inside the front of the shelf). This apparently fools the kami into thinking that it’s the sky above them, or maybe mollifies them because you’ve obviously made an effort.

These days, shrines are very clear that you do not need a traditional shelf for your kamidana, and, indeed, in our old flat I had it on top of my bookcases. This is because it is difficult to impossible to add a kamidana to modern flats, and, despite the name, the shelf is not actually the important part.

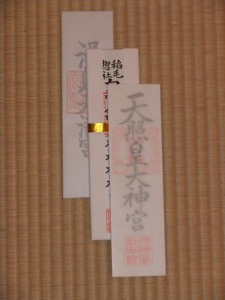

The important part is the o-fuda. O-fuda are obtained from shrines, either directly, by visiting and making an offering (usually about 1,000 yen, which is about $12.50 at the moment), or, in the case of the o-fuda of the Grand Shrines of Ise, which are called Jingū Taima, from any shrine affiliated with Jinja Honchō. Physically, an o-fuda is a thin wooden board wrapped in paper, about 25cm long and about 8cm wide, with the name of the shrine or kami written in black, with the red seal of the shrine over that.

The important part is the o-fuda. O-fuda are obtained from shrines, either directly, by visiting and making an offering (usually about 1,000 yen, which is about $12.50 at the moment), or, in the case of the o-fuda of the Grand Shrines of Ise, which are called Jingū Taima, from any shrine affiliated with Jinja Honchō. Physically, an o-fuda is a thin wooden board wrapped in paper, about 25cm long and about 8cm wide, with the name of the shrine or kami written in black, with the red seal of the shrine over that.

The question of what they are religiously is controversial, because Shinto tends to be vague on central points like this. They may be purely symbolic. However, in general they seem to be taken to be dwelling places of the kami in question; the kami is thought to be present in the o-fuda, and hence on the kamidana. That’s why the o-fuda is the most important part of the kamidana, because without it you have no kami on your kami shelf.

There are three classes of o-fuda on a standard contemporary kamidana. The first is the Jingū Taima, representing Amaterasu Ōmikami, of the Grand Shrines of Ise. The Association of Shinto Shrines insists that every kamidana should have one of these, and that it should be placed in the most honourable position. The second is the o-fuda of the household’s ujigami-sama, or local tutelary deity. In most cases, this means the o-fuda of your closest shrine, although there are some cases where the shapes of the regions covered by a shrine mean that the ujigami-sama is not actually the closest shrine. In our case, it means the o-fuda of Shirahata Hachiman Daijin, which is, obviously, a Hachiman shrine. This o-fuda goes in the second place. The final class is the o-fuda of shrines you, personally or as a family, respect or have links to. These can be any shrines; in our case, it is Yushima Tenmangū, which is the shrine where Yuriko and I got married. These o-fuda go in last place, and it is often said that you shouldn’t have too many of them.

Because the o-fuda may embody the kami, they are supposed to be treated with respect, and not just piled up on the shelf. Shrines provide free simple stands for them, but it’s much nicer to get a miyagata, which means “shrine model”, to hold them. This is, astonishingly, a wooden model of a shrine, and the o-fuda go inside. Although the miyagata normally does have doors on the front, like a shrine, you can’t normally get the o-fuda in through the doors, as the inside of the miyagata is not much bigger than the o-fuda. There are various ways to solve this problem, but in our case, the front of the miyagata comes off altogether, giving easy access to the interior.

Because the o-fuda may embody the kami, they are supposed to be treated with respect, and not just piled up on the shelf. Shrines provide free simple stands for them, but it’s much nicer to get a miyagata, which means “shrine model”, to hold them. This is, astonishingly, a wooden model of a shrine, and the o-fuda go inside. Although the miyagata normally does have doors on the front, like a shrine, you can’t normally get the o-fuda in through the doors, as the inside of the miyagata is not much bigger than the o-fuda. There are various ways to solve this problem, but in our case, the front of the miyagata comes off altogether, giving easy access to the interior.

When the o-fuda go in a simple, one-space miyagata like ours, the place of honour is at the front, so that the Jingū Taima goes in front, with the ujigami-sama o-fuda behind it, and the o-fuda of other shrines behind both of them. The o-fuda in the photograph above are in the right order. Miyagata with three chambers are also quite common, and in that case the place of honour is the centre, with the space to the right as you look at it as the second place, for the ujigami-sama, and the space to the left for the other shrines. It is also possible to get miyagata with five or seven spaces, and while the central position is still the first, I’m not sure whether all the spaces to the right are ahead of all the ones to the left, or whether it alternates, so that the fourth most honourable location is the second on the right. Miyagata with that many spaces are really not common, because not many people have enough space for them.

When the o-fuda go in a simple, one-space miyagata like ours, the place of honour is at the front, so that the Jingū Taima goes in front, with the ujigami-sama o-fuda behind it, and the o-fuda of other shrines behind both of them. The o-fuda in the photograph above are in the right order. Miyagata with three chambers are also quite common, and in that case the place of honour is the centre, with the space to the right as you look at it as the second place, for the ujigami-sama, and the space to the left for the other shrines. It is also possible to get miyagata with five or seven spaces, and while the central position is still the first, I’m not sure whether all the spaces to the right are ahead of all the ones to the left, or whether it alternates, so that the fourth most honourable location is the second on the right. Miyagata with that many spaces are really not common, because not many people have enough space for them.

Once the o-fuda are in the miyagata, you can close it up and put the kami on the kami shelf. The miyagata goes in the centre of the shelf, towards the back. Next, you can put other things on the shelf.

Once the o-fuda are in the miyagata, you can close it up and put the kami on the kami shelf. The miyagata goes in the centre of the shelf, towards the back. Next, you can put other things on the shelf.

The kamidana should, unsurprisingly, not be used for normal storage. You should also really not use it as a place to hang washing, but the kami seem to be quite forgiving about that, and I do encourage Yuriko to move it as soon as possible. However, there are certain things that you are supposed to put on the shelf.

First, when you go to a shrine and have a formal prayer performed in the worship hall (haiden), you usually receive a wooden o-fuda, which is a bit bigger than the ones that normally go in a miyagata, and which typically has your name and the purpose of the prayer written on. These o-fuda should be kept on the kamidana. In general, you are supposed to return the o-fuda to the shrine that issued them after a year, or more generally at the new year after you receive the o-fuda. If you got an o-fuda from the other end of Japan while you were on holiday, returning it to your local shrine is acceptable. However, I don’t do that for o-fuda that mark important events. So, for example, the o-fuda from our wedding and Mayuki’s Hatsumiyamairi are still on the kamidana. However, when we went to Shirahata-san this afternoon for a new year prayer, we got an o-fuda marked “First Prayer”, and I will take that back next year. After all, we’ll get another one. In any case, these o-fuda are supposed to be kept on the kamidana, next to the miyagata, until you take them back.

First, when you go to a shrine and have a formal prayer performed in the worship hall (haiden), you usually receive a wooden o-fuda, which is a bit bigger than the ones that normally go in a miyagata, and which typically has your name and the purpose of the prayer written on. These o-fuda should be kept on the kamidana. In general, you are supposed to return the o-fuda to the shrine that issued them after a year, or more generally at the new year after you receive the o-fuda. If you got an o-fuda from the other end of Japan while you were on holiday, returning it to your local shrine is acceptable. However, I don’t do that for o-fuda that mark important events. So, for example, the o-fuda from our wedding and Mayuki’s Hatsumiyamairi are still on the kamidana. However, when we went to Shirahata-san this afternoon for a new year prayer, we got an o-fuda marked “First Prayer”, and I will take that back next year. After all, we’ll get another one. In any case, these o-fuda are supposed to be kept on the kamidana, next to the miyagata, until you take them back.

The second class of things that you keep on the kamidana are the so-called “engimono”, “good luck things”. This includes o-mamori, which are amulets issued by shrines for various purposes, and other similar items. One that you can see in the photograph, on the left, is a hamaya, a good-luck arrow that shrines distribute at new year. (The meaning of the name is disputed, but it is normally written with the characters for “magic destroying arrow”.) Most of these items are also supposed to be returned to a shrine after a year; again, I don’t always. Sometimes they have significant meanings, such as the two o-mamori Yuriko and I got when we performed a ceremony to announce our wedding at Shirahata-san. Sometimes, they’re interesting, and from shrines hundreds of kilometres away that I’m unlikely to visit again. The hamaya, however, does go back to Shirahata-san every year.

The second class of things that you keep on the kamidana are the so-called “engimono”, “good luck things”. This includes o-mamori, which are amulets issued by shrines for various purposes, and other similar items. One that you can see in the photograph, on the left, is a hamaya, a good-luck arrow that shrines distribute at new year. (The meaning of the name is disputed, but it is normally written with the characters for “magic destroying arrow”.) Most of these items are also supposed to be returned to a shrine after a year; again, I don’t always. Sometimes they have significant meanings, such as the two o-mamori Yuriko and I got when we performed a ceremony to announce our wedding at Shirahata-san. Sometimes, they’re interesting, and from shrines hundreds of kilometres away that I’m unlikely to visit again. The hamaya, however, does go back to Shirahata-san every year.

Finally, there are the standard “furnishings” for a kamidana. The first of these is two bunches of sakaki twigs. Sakaki is an evergreen tree endemic to Japan, and it is used in a lot of Shinto ceremonies. The sakaki in the picture is new year sakaki, and you may be able to see that there are pine branches in the front; regular sakaki doesn’t have those. You are supposed to change the sakaki every two weeks, on the first and fifteenth of the month, and for a few days before that florists in Japan sell prepared sakaki bundles. If you forget to buy replacements, the sakaki tends to look very forlorn by the time they come round again. On the old Japanese lunar calendar, the first and fifteenth (or sixteenth) were the new and full moons, respectively, but these days the replacement is done according to the solar calendar, and so has nothing to do with the moon.

Finally, there are the standard “furnishings” for a kamidana. The first of these is two bunches of sakaki twigs. Sakaki is an evergreen tree endemic to Japan, and it is used in a lot of Shinto ceremonies. The sakaki in the picture is new year sakaki, and you may be able to see that there are pine branches in the front; regular sakaki doesn’t have those. You are supposed to change the sakaki every two weeks, on the first and fifteenth of the month, and for a few days before that florists in Japan sell prepared sakaki bundles. If you forget to buy replacements, the sakaki tends to look very forlorn by the time they come round again. On the old Japanese lunar calendar, the first and fifteenth (or sixteenth) were the new and full moons, respectively, but these days the replacement is done according to the solar calendar, and so has nothing to do with the moon.

Next, there are three things that I don’t have on my kamidana. First, it is common to have a polished metal mirror in front of the doors to the shrine. This is because a mirror is a very common symbol of the kami, most famously of Amaterasu. Second, people often have light sources, generally electric these days because of the risk of fire, to either side of the miyagata. Finally, a shimenawa, or sacred rope, across the top is also common. We don’t have one of them because I haven’t sorted out how to fix it yet. The mirror and the lights are missing because I haven’t been able to afford them yet…

Finally, there are the offerings to the kami. These offerings should not be placed directly on the kamidana, but instead on a special tray called a “sanbō”. The name means “three directions”, and comes from the fact that there are decorative holes in three sides of the base. The side of the base without a hole is the front, and should be placed facing towards the kami. The offerings are placed on top of it, often, as here, in white ceramic containers. There are four standard offerings.

Finally, there are the offerings to the kami. These offerings should not be placed directly on the kamidana, but instead on a special tray called a “sanbō”. The name means “three directions”, and comes from the fact that there are decorative holes in three sides of the base. The side of the base without a hole is the front, and should be placed facing towards the kami. The offerings are placed on top of it, often, as here, in white ceramic containers. There are four standard offerings.

The first is rice. This can be cooked or not, although we normally offer it uncooked, because it keeps longer. This is the most important of the offerings, and is placed nearest to the kami.

The second is sake, rice wine. This is next in importance, and it is normal to have two bottles of sake in the offerings.

The second is sake, rice wine. This is next in importance, and it is normal to have two bottles of sake in the offerings.

Finally, water and salt are offered, and these two are furthest away from the kami.

In principle, you are supposed to change the offerings every day, but that doesn’t happen at our house; they get changed when I change the sakaki, so normally every two weeks. Normally, you eat the things that have been offered to the kami after they are taken down, but because the rice has been sitting out in the open for a couple of weeks, I just throw it away. The sake, however, is poured into a jar to be used later; the sake jars, as you can see, have lids, so it is fine.

[Edit 2021/01: Well, I wrote that ten years ago and it is no longer true. I would not recommend that anymore, even though it is standard practice and the form that some priests recommend; rather, I recommend that you put the offerings on the kamidana immediately before you pay your respects, and take them down immediately afterwards, so that there is no problem eating them. Paying your respects every day is still the ideal. My guide to Shinto Practice for Non-Japanese has more details, and my Mimusubi blog has more details on why this is not as straightforward as you might think.]

You can also offer other things to the kami, particular food that you don’t see very often. Rice, water, salt, and sake are the staples, so seasonal vegetables and sea food are standard offerings. It is unusual, although not unheard of, to offer meat to the kami. You can also offer inedible things, like books or flowers. As with the standard offerings, you would use the item after it is taken down; that is, in fact, the main point. A central part of Shinto worship is the common meal with the kami, where you eat the food offered to them.

The offerings are placed on the kamidana, in front of the miyagata, which is why it is placed towards the back. Once the offerings are in place, the kamidana is complete, and you can properly venerate the kami at your own household shrine.

Since writing this article, I have written An Introduction to Shinto, and a guide to Shinto Practice for Non-Japanese, both available from Amazon. I’m also writing a series of in-depth essays on Shinto, supported through Patreon. If you are interested in learning more about Shinto, I invite you to have a look, and consider becoming a patron.

Leave a Reply